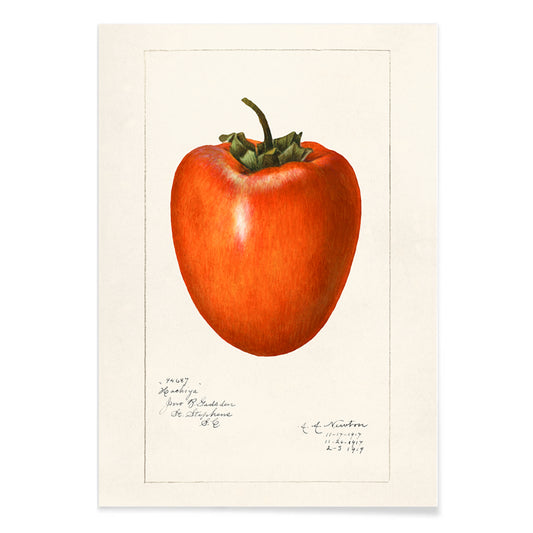

- Persimmons Poster

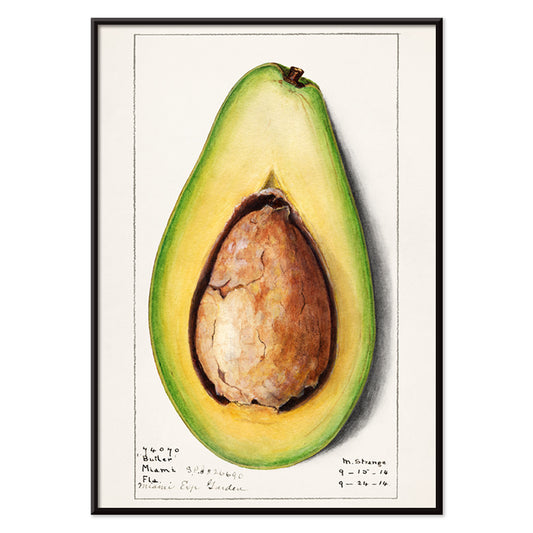

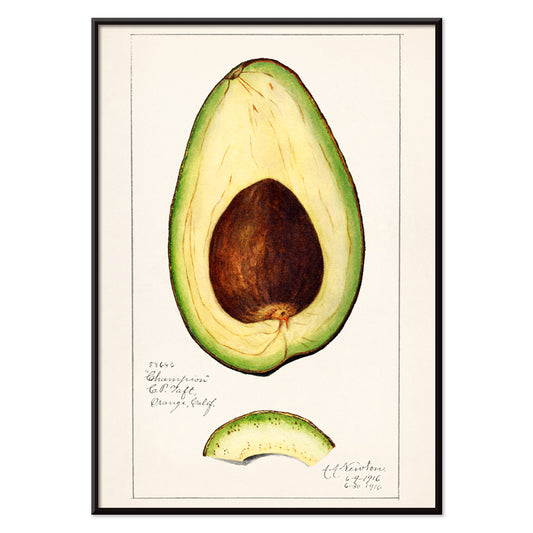

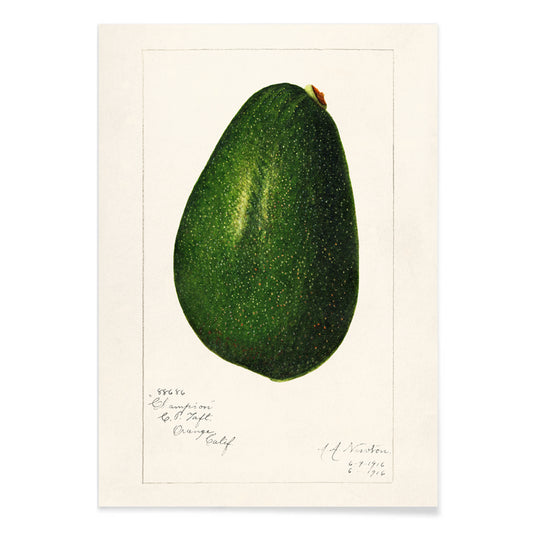

- Avocado (Persea) Poster

- Avocado (Persea) Poster

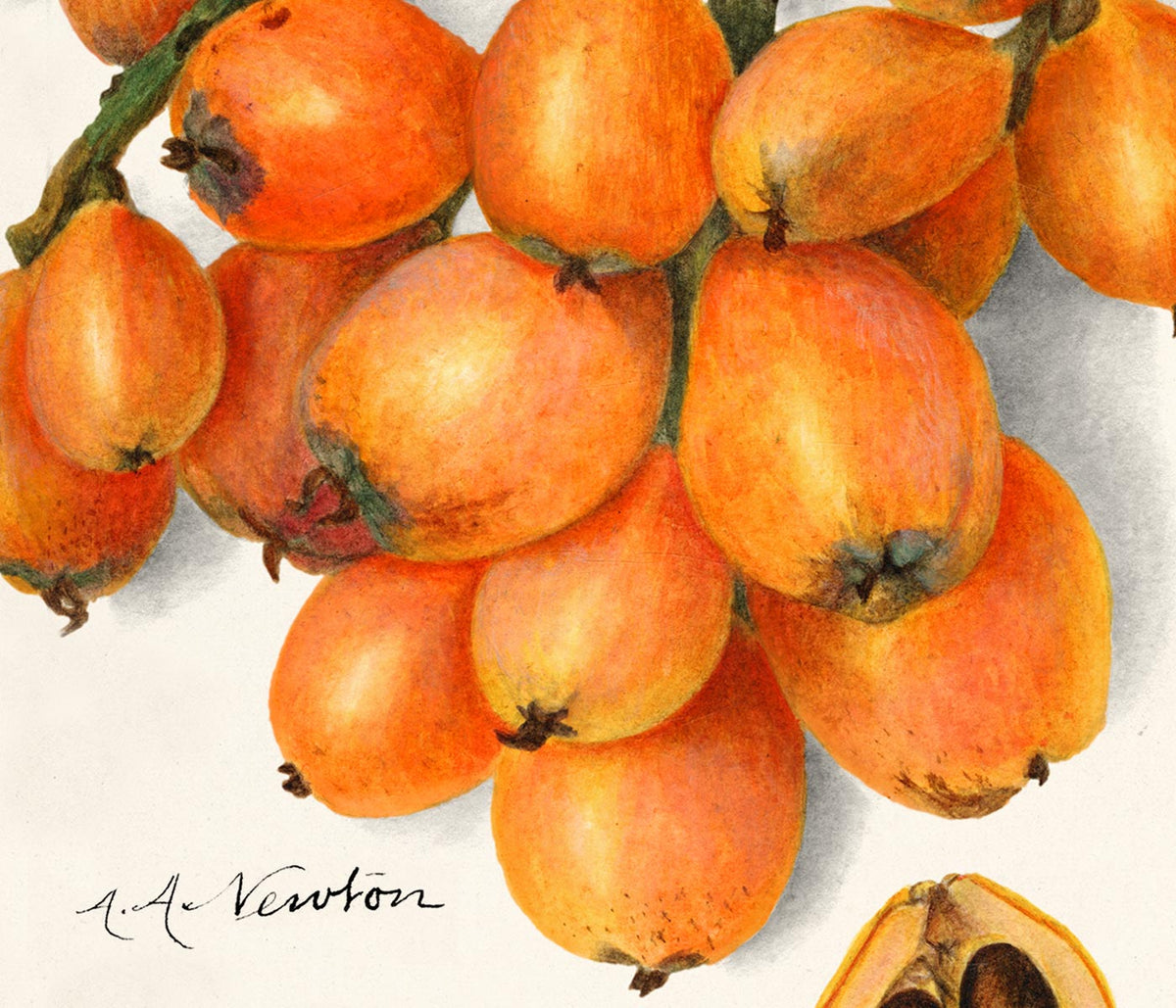

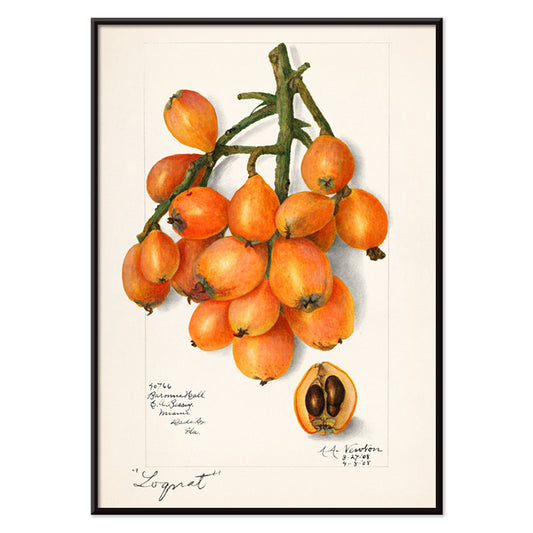

- Loquats (Eriobotrya Japonica) Poster

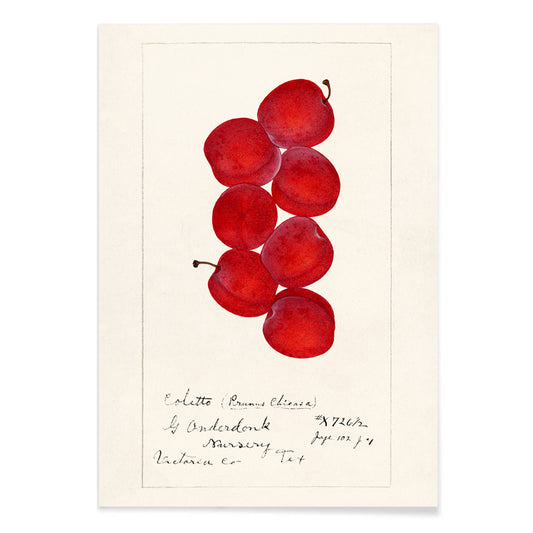

- Prunus Domestica Poster

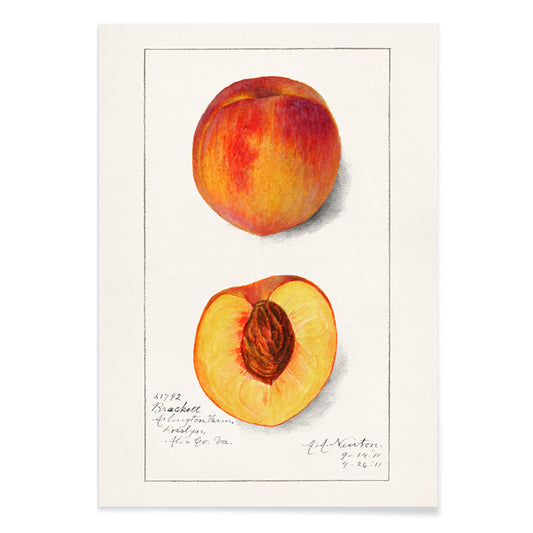

- Prunus Persica Poster

- Fragaria Poster

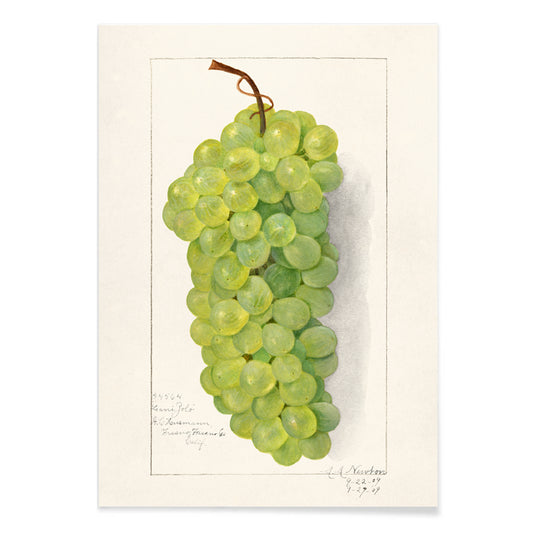

- Bunch of green grapes Poster

- Avocado Persea Poster

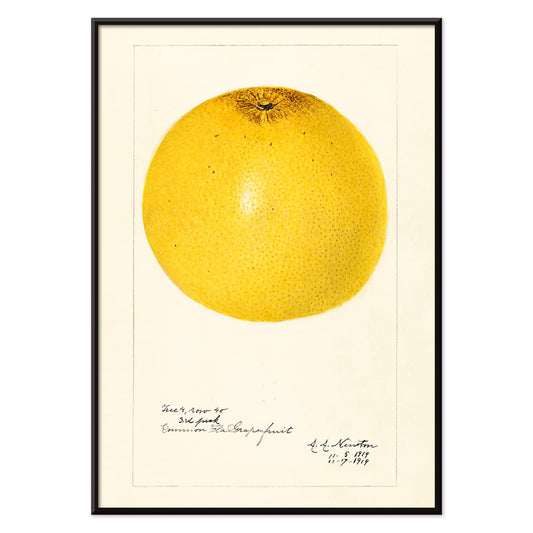

- Malus Domestica Poster

- Malus Domestica Poster

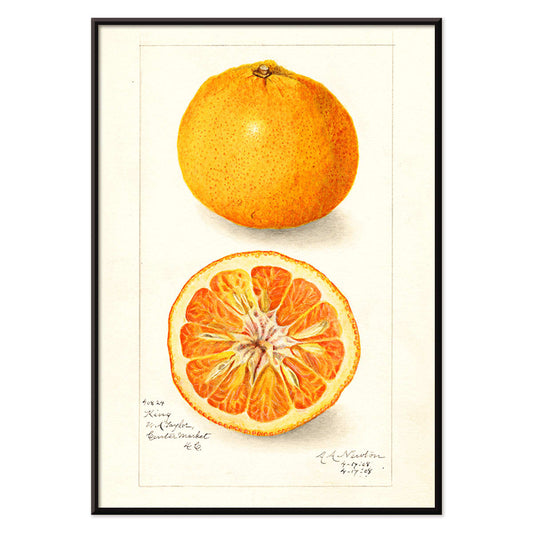

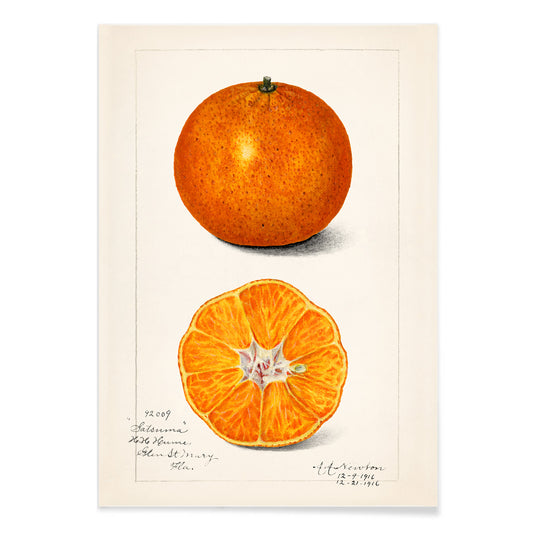

- Citrus Sinensis Poster

- Walnuts Poster

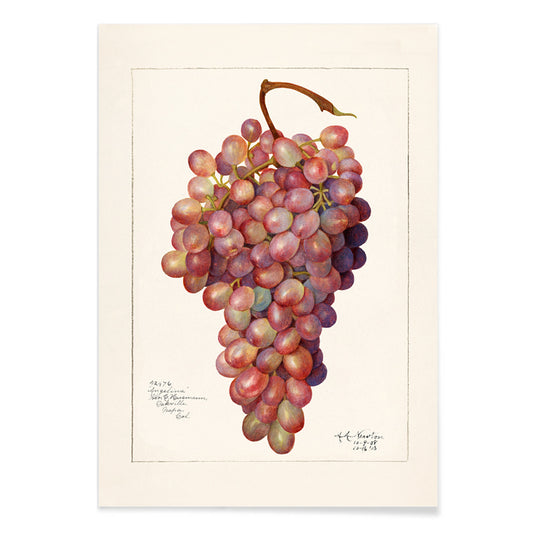

- Vintage bunch of red grape Poster

- Persimmons Poster

- Avocado (Persea) Poster

- Avocado (Persea) Poster

- Loquats (Eriobotrya Japonica) Poster

- Prunus Domestica Poster

- Prunus Persica Poster

- Fragaria Poster

- Bunch of green grapes Poster

- Avocado Persea Poster

- Malus Domestica Poster

- Malus Domestica Poster

- Citrus Sinensis Poster

- Walnuts Poster

- Vintage bunch of red grape Poster

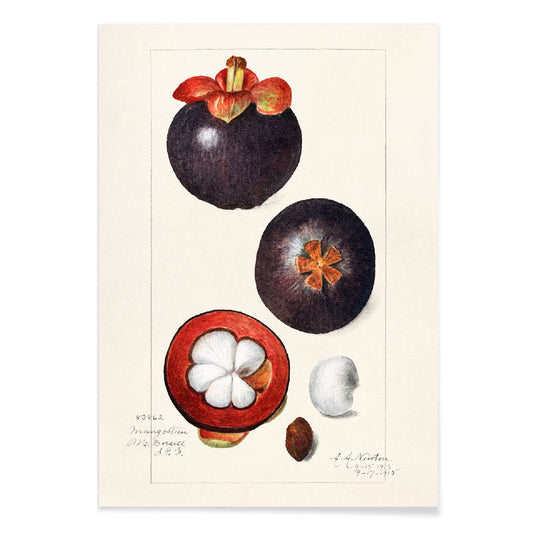

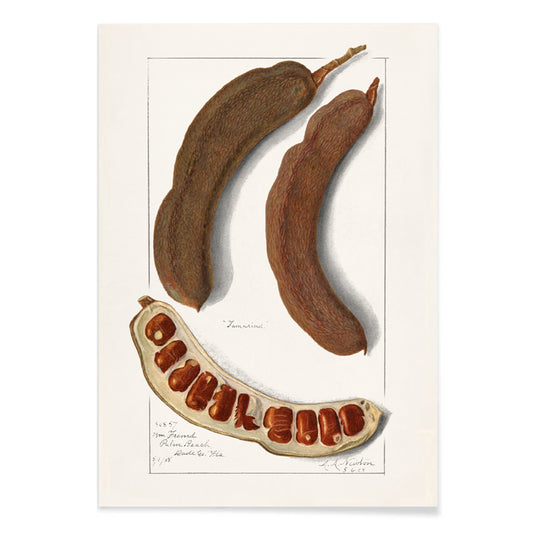

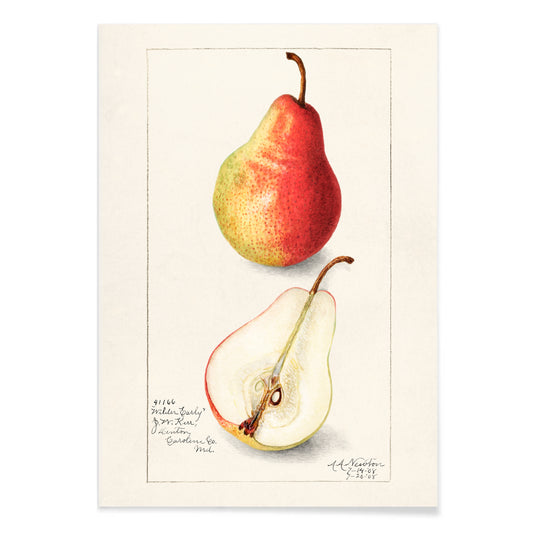

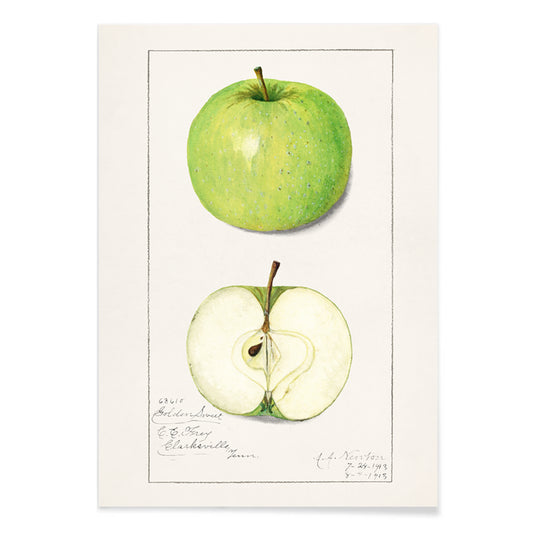

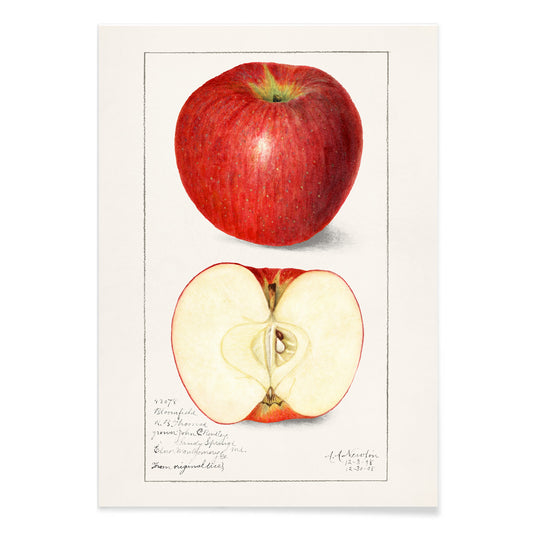

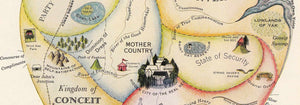

A botanical pantry in watercolor

In the early twentieth century, botanical illustration often sat between laboratory discipline and domestic delight, and Amanda Almira Newton’s fruit studies inhabit that middle ground. Her images read like working notes made with patience: an object isolated, observed, and left to speak for itself. As posters, the compositions keep a deliberate calm, using open paper as part of the design rather than empty space to be filled. The result is vintage wall art that feels equally at home beside cookbooks and ceramics, and it sits naturally near related themes in Botanical, Science, and the broader context of Famous Artists.

Newton’s approach: observation, spacing, and wash

Newton worked in watercolor with a clarity that prioritizes contour, surface, and scale over drama. The paint stays translucent so the fruit remains readable as specimen, not theatrical still life. Egon Schiele once used blank paper as tension; Newton uses it as quiet measurement, letting the viewer compare shape, rind, and flesh without distraction. In Avocado (Persea) (1916), the halved fruit becomes a small lesson in structure: pale greens, a firm outline, and the pit acting like a weight at the center. Strawberries (Fragaria) (1912) shifts the register toward brightness, where seeds, blossoms, and serrated leaves keep sweetness grounded in botany.

Interior placement: kitchen light and dining materials

Because the imagery is straightforward and the palette stays gentle, these prints settle into rooms with active surfaces. In a kitchen, they pair well with tile grids, butcher-block warmth, and brass or steel hardware, echoing the functional order of Kitchen interiors without becoming signage. In a dining room, hang one poster above a sideboard so the white space can catch daylight and the pigments can read true rather than muddy. If the room is built around light woods, linen, and stoneware, pull supporting tones from Beige; if you want crisper contrast, a restrained companion from Black & White can sharpen the wall without fighting the fruit colors.

Curating a series: rhythm, scale, and frames

A good group relies on visual rhythm: round forms against branching diagonals, reds against greens, smooth skins against cracked shells. Loquats (Eriobotrya Japonica) (1908) brings an elegant slant that leads the eye along stem and leaf, while Walnuts (Juglans) (1911) lowers the tempo with earthier browns and a more tactile subject. Keep spacing consistent and use mats to preserve the archive-sheet feeling. Thin oak frames warm the paper; black metal frames emphasize line and labeling. For a cohesive finish across a gallery wall, coordinate formats through Vertical Posters or explore practical options in Frames.

Collecting fruit as an archive of attention

Newton’s fruit studies are persuasive because they refuse symbolism and instead reward attention: you notice bloom, bruising, and the slight shadow under a stem. As vintage posters, they offer decoration that behaves like a record, not a slogan. Leave generous margins, let paper texture show, and the wall art will feel closer to a kept notebook page than to a loud display.