A small universe of signs and color

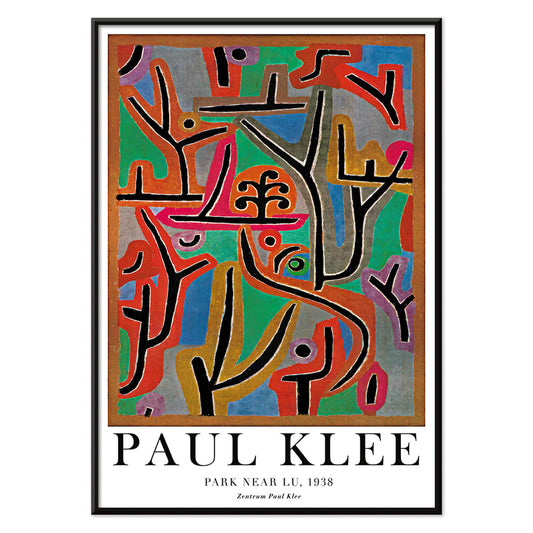

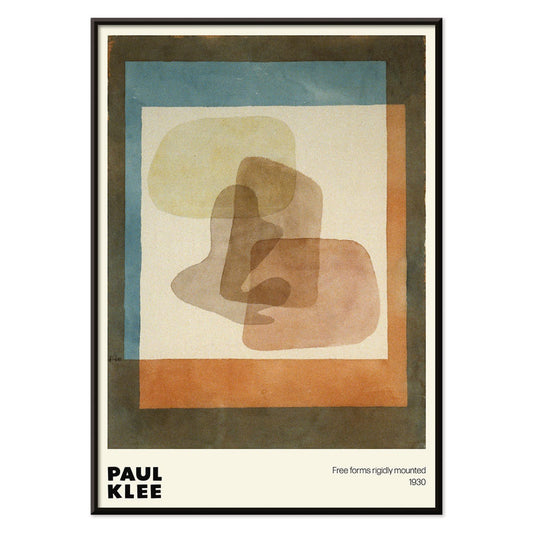

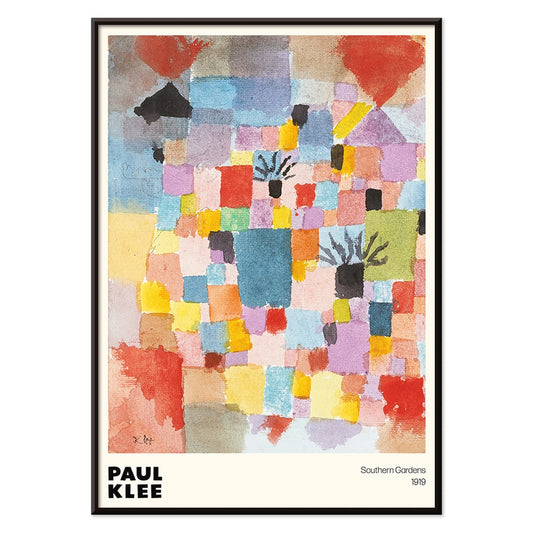

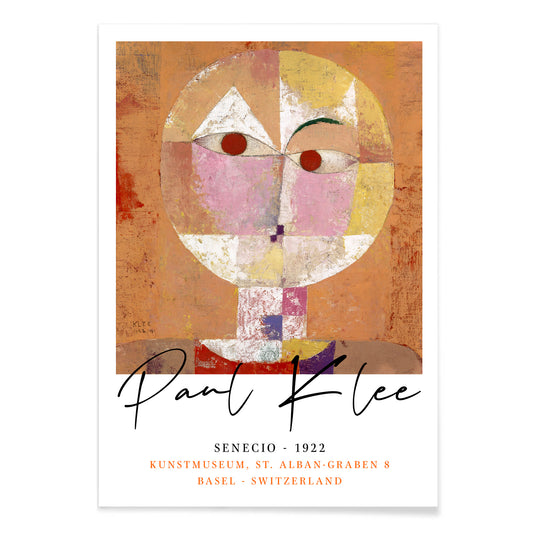

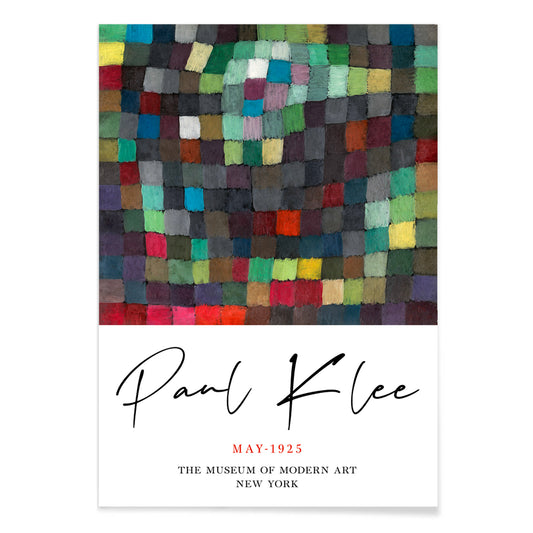

Paul Klee’s pictures hover between childlike immediacy and strict construction: arrows, grids, trees, and drifting constellations arranged with measured pauses. From 1914 to 1938, his vocabulary grew into a kind of portable cosmology, well suited to poster and art print formats where paper texture and thin washes stay legible. Klee passed through Expressionism and Cubism, absorbed a Surrealist edge, and still kept his own syntax of symbols. For related visual languages, the abstract and classic-art collections show how modernism negotiated between invention and tradition.

Klee’s methods: watercolor, line, and music

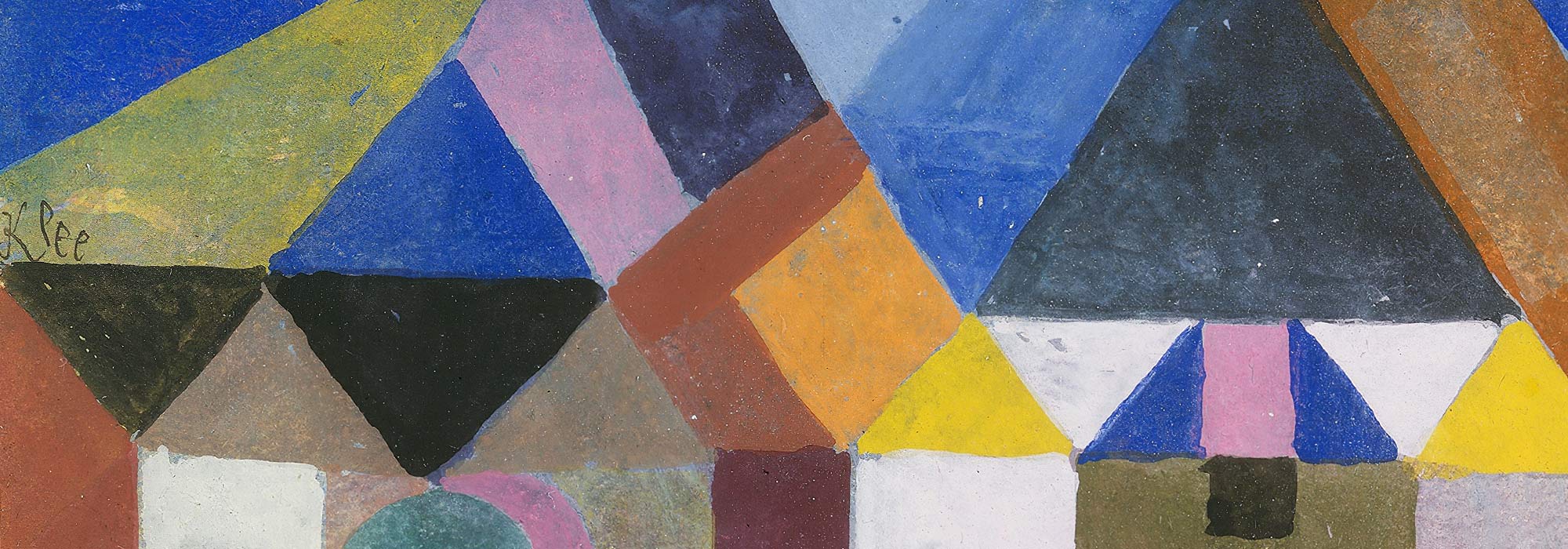

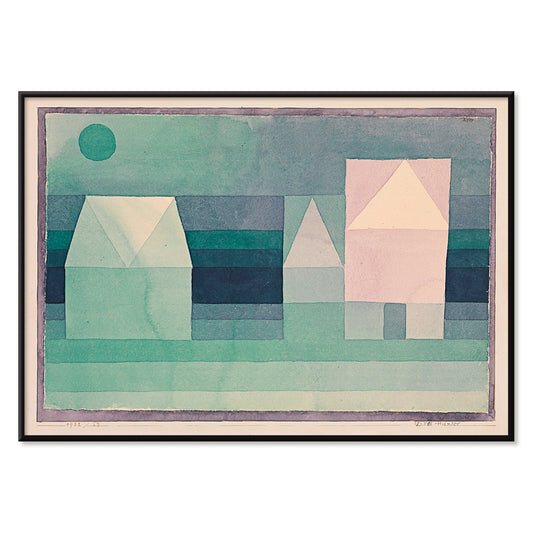

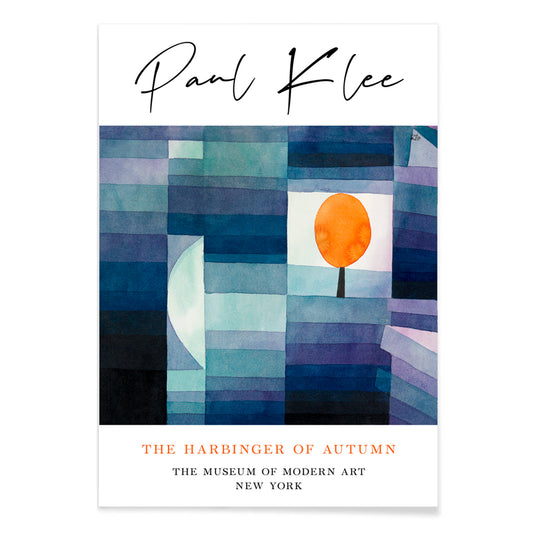

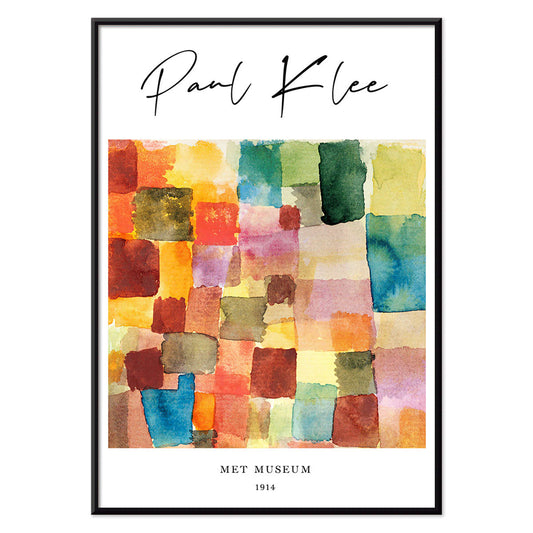

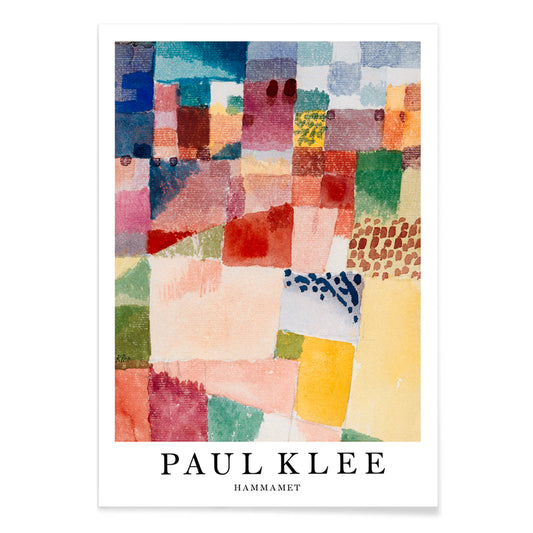

Klee treated technique as thinking aloud. In The Harbinger of Autumn (1922), a flame-orange tree stands like an emblem against a calmly partitioned ground, a single motif carrying the whole season. He often layered watercolor beneath pencil, letting stain and resistance create a living surface; corrections remain visible as part of the image rather than something to erase. His titles act like musical markings, nudging mood and tempo. The Tunisian journey of 1914 sharpened his sense of luminous structure, and Motif from Hammamet (1914) turns architecture into a mosaic of sand, sea, and rose notes. Nearby, bauhaus context helps explain the analytical side of his play: exercises in rhythm, proportion, and balance.

Design notes for home decor

Klee works best when treated as a calibrated accent rather than a focal shout. In a dining nook, watercolor passages sit comfortably with pale oak, linen, and matte ceramics; in a study, his thin linework mirrors shelving, desk lamps, and the geometry of a work surface. If your room leans minimalist, choose one mid-sized print and leave generous wall space so the small marks can be read up close. In more layered interiors, a Klee poster can soften sharp furniture edges and introduce a measured, vintage inflection without turning the room into a period set. Warm whites, plaster textures, brass, terracotta, and sage pull out his quieter pigments while keeping the overall decoration restrained.

Curating a gallery wall around Klee

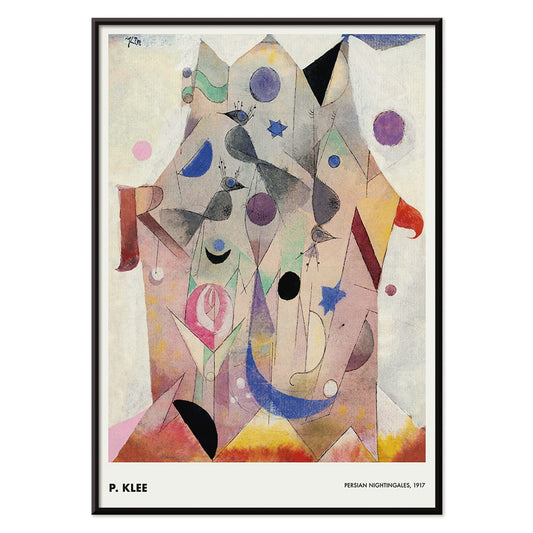

A Klee-centered gallery wall benefits from contrasts in density and material. The airy, avian patterning of Persian Nightingales (1917) pairs well with stricter geometry, making the surrounding pieces feel intentionally structured rather than merely assorted. For a hotter note, Poisonous Berries (1920) can sit beside monochrome work so its reds and violets register as a controlled pulse. If you want a broader modernist conversation, place Klee among famous-artists selections. Thin oak or matte black mouldings keep the line delicate, and the frames collection supports either a clean white mat for emphasis or an un-matted edge for a studio-sheet feel.

Why Klee still feels current

Klee is often described as playful, but the durability comes from discipline: each dot, square, and wavering line is positioned to hold tension without clutter. In wall art form, that intimacy reads like a note passed between artist and viewer, rewarding repeat glances in hallways, kitchens, or work corners. For homes that want decoration with curiosity rather than noise, his prints offer a quietly structured way to live with abstraction.